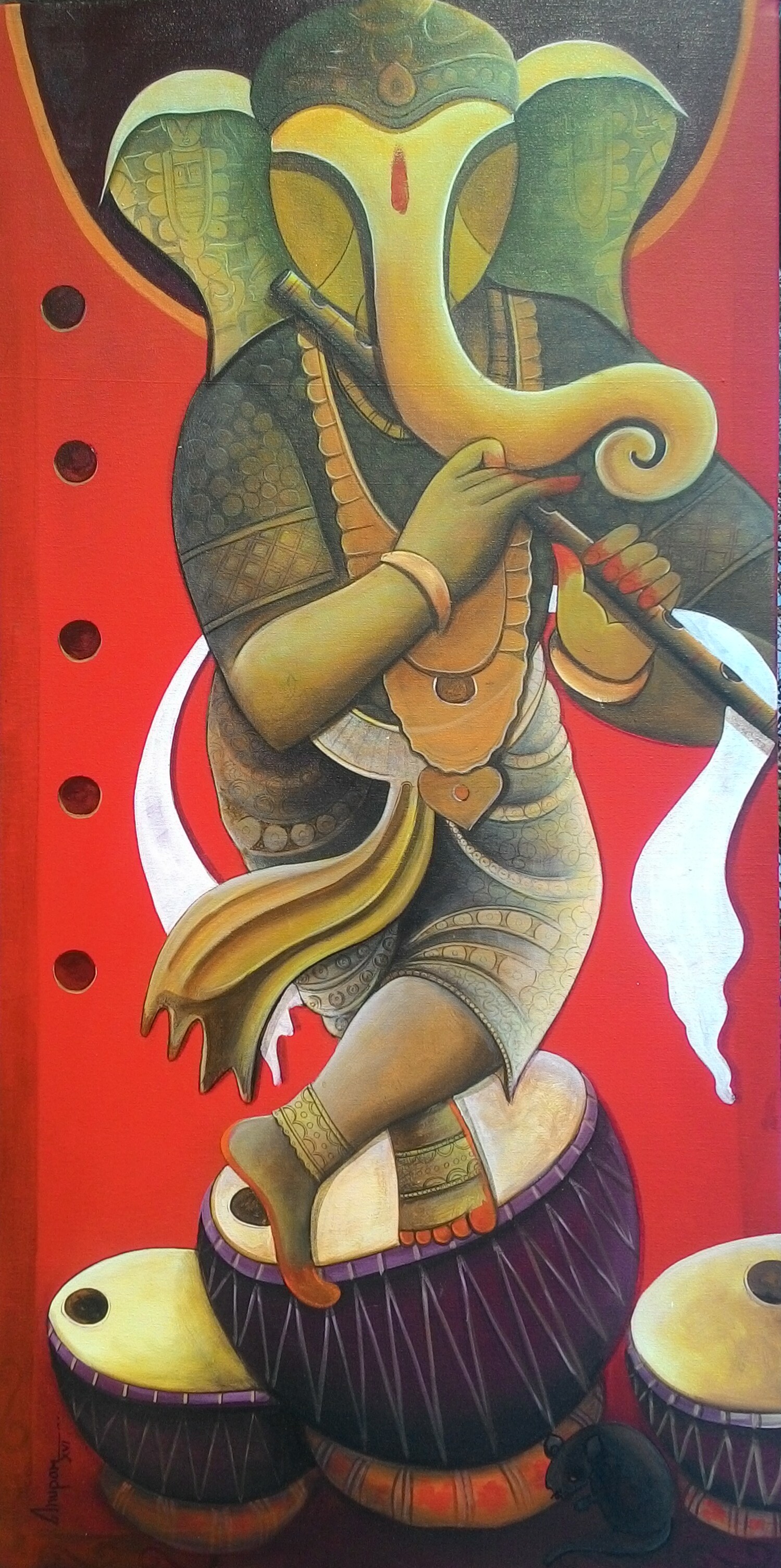

If you are an art lover who loves to visit every art gallery in your vicinity, then you must have observed that over the last few years there has been a surge in the number of religious themed paintings. From vivid Ganesha paintings to the paintings depicted the divine love of deities; all sort of paintings are available in the market. Intrigued by the overwhelming presence of religious painting, I decided to dig deep into the history and association of religion and art. It was only a matter of few hours that I realized that it has only been the last few hundred years or so that Western civilization has been putting art in museums, at least museums resembling the public institutions we know today. Before this, for most, art served other purposes. What we call fine art today was, in fact, primarily how people experienced an aesthetic dimension of religion.

Paintings, sculpture, textiles and illuminations were the media of their time, supplying vivid imagery to accompany the stories of the day. In this sense, Western art shared a utilitarian purpose with other cultures around the world, some of whose languages incidentally have no word for art. So, the next question that arises is: how do we define what we call art.

Generally speaking, what we are talking about here is creative work that visually communicated meaning beyond language, either through representation or arrangement of visual elements in space. Evidence of this power of iconography or the ability of images to convey meaning, can be found in abundance if we look at art from histories of the major world religions. Almost all have, at one time or another in their history, gone through some sort of aniconic phase.

Aniconism prohibits any visual depiction of the divine. This is done in order to avoid idolatry, or confusion between the representation of divinity and divinity itself. However, this could be a challenge to maintain given that the urge to visually represent and interpret the world around us is a compulsion difficult to suppress. For example, while Hinduism permits the depiction of lords in paintings, like depiction of Lord Ganesha in Ganesha paintings, Islam prohibits the depiction of Allah or the Prophet Muhammad; however, an abstract celebration of the divine can still be found in arabesque patterns of Islamic textile design, with masterful flourishes of brushwork and Arabic calligraphy where the words of Prophet assume a dual role as both literature and visual art. Likewise, in art from the early periods of Christianity and Buddhism, the divine presence of the Christ and the Buddha do not appear in human form, but are represented by symbols. In each case, iconographic reference is employed as a form of reverence. Anthropomorphic representation or depiction in human form eventually became widespread in these religions only centuries later, under the influence of the cultural traditions surrounding them.

Historically speaking, the public appreciation of visual art in terms other than traditional, religious or social function is relatively new concept. Today, we fetishize the fetish, so to speak. We go to museums to see art from the ages, but our experience of it there is drastically removed from the context in which it was originally intended to be seen. It might be said that the modern viewer lacks the richness of engagement that he/she has with contemporary art, which has been created relevant to their time and speaks their cultural language. It might also be said that the history of what we call art is a conversation that continues on, as our contemporary present passes into what will be some future generation’s classical past.

It is a conversation that reflects the ideologies, mythologies, belief systems and taboos and so much more of the world in which it was made. But this is not to say that work from another age made to serve a particular function in that time is dead or has nothing to offer the modern viewer. Even though in a museum setting works of art from different places and times are presented alongside each other, isolated from their original settings, their juxtaposition has benefits. Exhibits are organized by curators, or people who have made a career out of their ability to re-contextualize or remix cultural artifacts in a collective presentation. As viewers, we are then able to consider the art in terms of a common theme that might not be apparent in a particular work until you see it alongside another, and new meanings can be derived and reflected upon. If we are so inclined, we might even start to see every work of art as a complementary part of some undefined, unified whole of past human experience, a trail that leads right to our doorstep and continues on with us, open to anyone who wants to explore it.